Understanding Transformers I - The Decoder

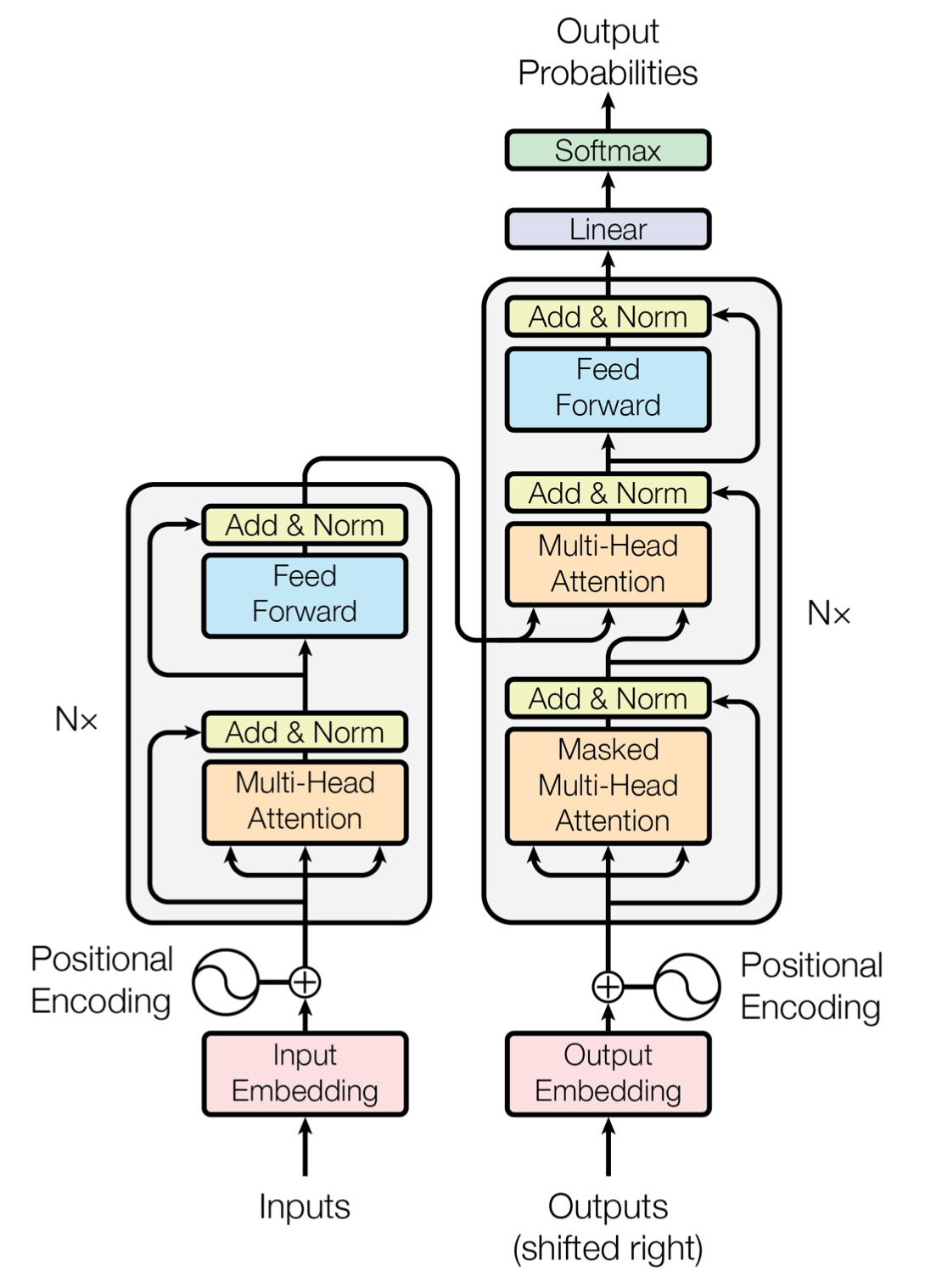

In this blog post I give an introduction to the Transformer architecture as originally presented by Vaswani et al., in their landmark paper, “Attention Is All You Need”. My focus will be on visuals and intuition. Specifically, I intend to explain the Transformer in three parts: Decoders, Encoders, and Cross Attention. This blog post covers part one of this list.

Breaking it down - Decoders, Encoders, and Cross Attention

For reasons, decoder-only architectures such as GPT-2 (released in 2019) and encoder-only architectures such as BERT (released 2018) actually came after the original encoder-decoder transformer paper in 2017. Despite this chronology it is useful to focus on these simpler transformers and build our way up in future sections to eventually combine the encoders and decoders together (via Cross Attention) to form the original transformer.

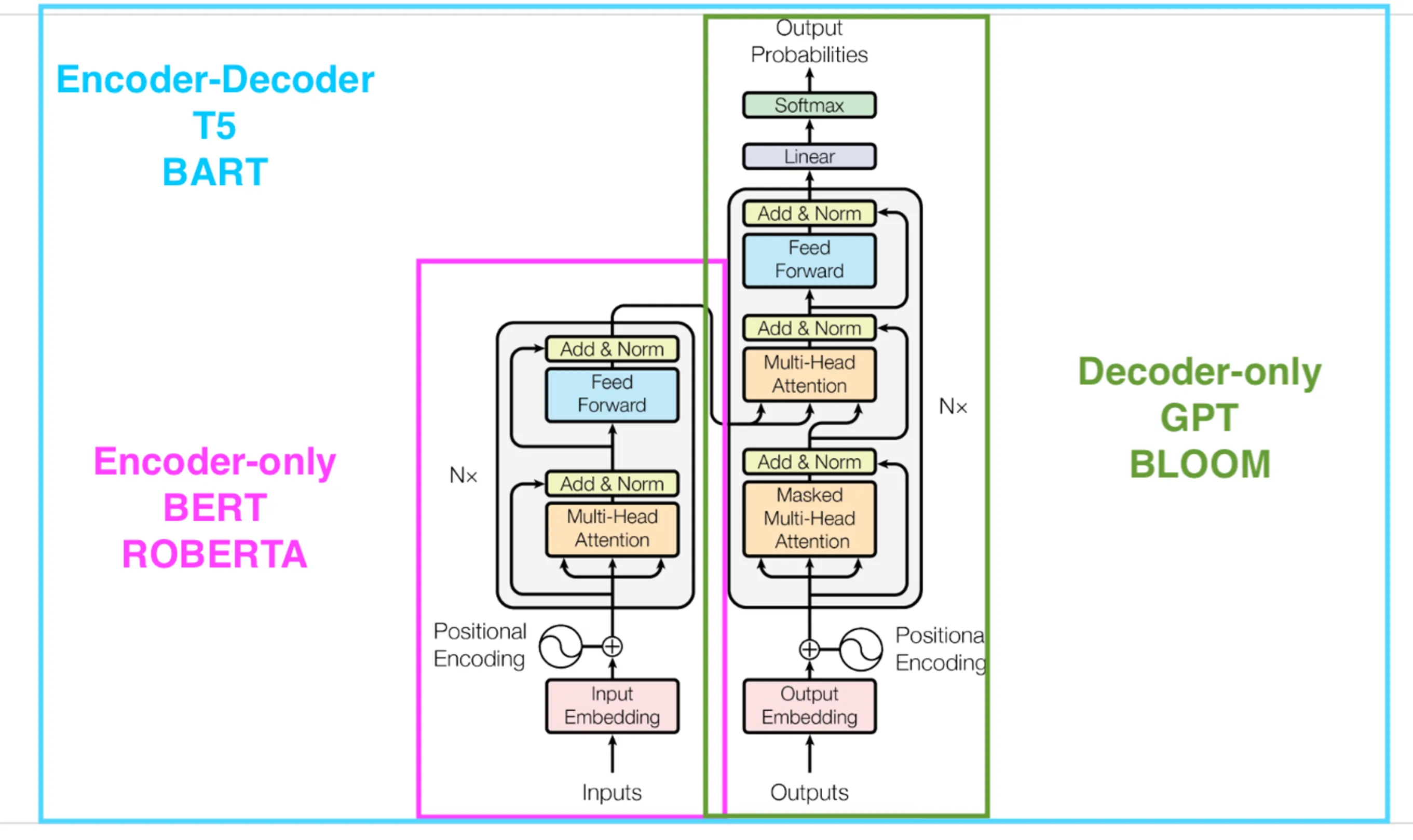

An easy way to visualize this is to divide the Transformer and relate it to these simpler transformers:

That is - Decoder only architectures mimic the right side of the Transformer stack, while encoder only architectures mimic the left side.

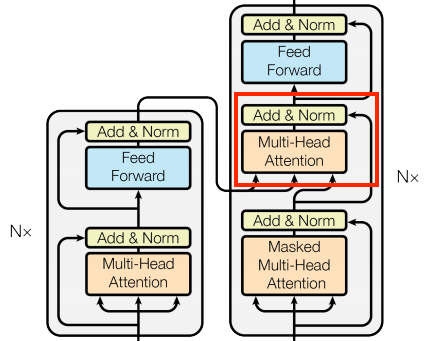

There is one subtle detail - in decoder only models i.e. the right side, there is of course no cross attention mechanism that connects the encoders to the decoders, so the second multi-head attention unit should be removed:

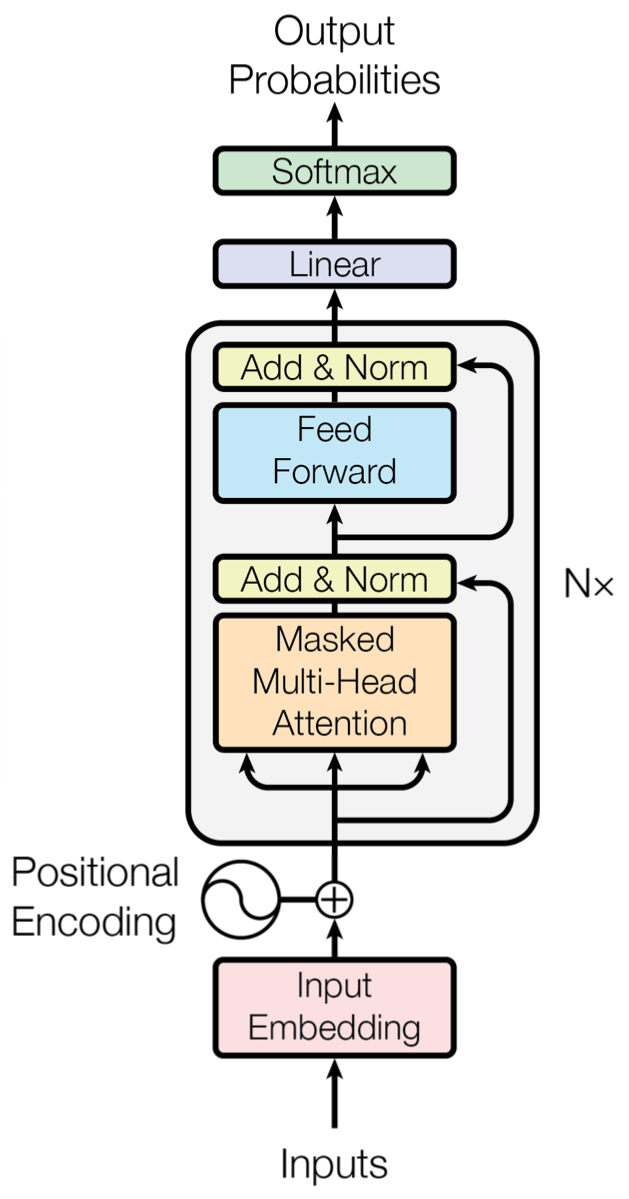

Therefore, a decoder-only transformer would look like this:

You may notice that this looks very similar to the encoder block, I will discuss the subtle differences in a separate post.

Decoder-only transformers - GPT-2

Let us now focus on the topic of this blog post which is Decoder-only architectures such as GPT-2. A model like this consumes a sentence and predicts the next token. In this sense, it can be understood that the Decoder architecture “decodes” what the next token should be, hence the name.

Some ideas below are inspired by the Transformer Explainer tool (Liang, D. & Klein, D.).

A model like this can be broken down into simple steps, each corresponding to a part of the diagram above:

-

Receive an input sentence: “Data visualization empowers users to”

- Tokenization and embeddings: For each token in the sentence, convert it to an embedding vector of fixed length.

- A token is a string of continuous characters treated as a unit. For example, in GPT-2’s tokenizer, ‘data’, ‘visualization’, ‘users’ and ‘to’ are all tokens. However, ‘em’ and ‘powers’ are separate tokens.

- An embedding is a vector that corresponds to the token, and represents its meaning.

-

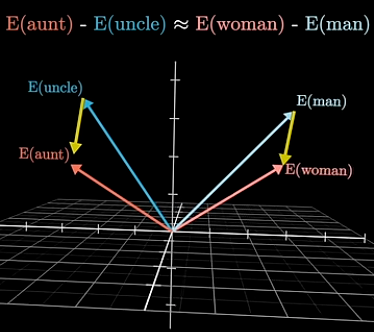

The embedding vector represents the token’s meaning in the sense that vector operations can be performed to produce similar concepts:

Figure 5. Subtracting the embedding vectors for man and women is equivalent to subtracting the embedding vectors for uncle and aunt (3Blue1Brown, 2024).

Figure 5. Subtracting the embedding vectors for man and women is equivalent to subtracting the embedding vectors for uncle and aunt (3Blue1Brown, 2024).

-

Positional encodings Special positional encoding vectors are added to each embedding to add meaning about the position of the token in the sentence. For example, there is a positional encoding vector for position 1, and it is added to the first token only.

- Attention: This corresponds to the “Masked Multi-head attention” box in the transformer diagram, it works as follows: For each embedding $\vec{e}$ (corresponding to an input token), apply special transforms (understood to be weights matrices, but this isn’t too important) $W_K$, $W_Q$, and $W_V$ to get the Key, Query, and Value vectors corresponding to the token, respectively. These matrices are learnt during the training process of the transformer.

- Such vectors can be understood as follows:

- The Key vector $\vec{k} = W_k \vec{e}$ is a vector of dimension $d_k$ such that when multiplied by another token’s Query vector, gives us a magnitude representing how much attention that other token is paying attention to us.

- The Query vector $\vec{q} = W_q \vec{e}$ is symmetrically a vector of dimension $d_q = d_k$ such that, when multiplied by another token’s Key vector, gives us a magnitude representing how much attention our token is paying attention to that other token.

- The Value vector $\vec{v} = W_v \vec{e}$ is a vector that represents the original embedding of the token in a new vector space, such that, when multiplied by attention (a scalar number), gives us a vector representing the original token scaled by the attention the current token has for it.

- To calculate the attention token $i$ has for token $j$, we could do something like this: $\vec{q_i}^\intercal \cdot \vec{k_j}$ thus getting a scalar number via the usual dot product. Then we could scale the value vector of token $j$, so that our scaled attention for token $j$ is just $\left(\vec{q_i}^\intercal \cdot \vec{k_j}\right) \vec{v_j}$.

- An astute reader would note that instead of doing each of these calculations as a for loop over all $i$ and $j$, we can get all of this together as one matrix mulitplication $Q^\intercal K V$, where $Q$, $K$, $V$ are matrices such that the ith column is the vector for the ith token.

-

The variance of the multiplication of $Q$ and $K$ happens to be $\sqrt{d_k}$ (user3667125, 2020). Then if we divide by this we can reduce the variance of the multiplication to 1. And we can then apply a softmax so that the sum of attention scores a token has for other tokens adds up to 1. This would give us $\text{softmax}\left( \frac{Q^\intercal K}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) V$.

- Therefore, for each input token’s embedding, we get a list of vectors that represent other vectors in the sentence, scaled by the attention this token has for them.

- This attention is called masked because we disallow tokens from paying attention to tokens ahead of it in the sentence, by zeroing out these values.

- This attention is called multi-head because technically, we run 12 of these attention heads in parallel, each doing the above as described, but for smaller sections of the input embeddings. For example, one attention head would look at the first 12th of each embedding. The second attention head would look at the second 12th of each embedding, etc. And then we just concatenate these results together to produce the same output had we done it all in one single head of attention.

- Such vectors can be understood as follows:

-

Once we have these scaled attention-value vectors, we run these through a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). This corresponds to the “Feed Forward” box in the transformer diagram (note: MLPs are only one type of Feed Forward network, but not all Feed Forward networks are MLPs). This adds many layers of non linearity that allows the transformer to learn deep features about these vectors.

-

Steps 4-5 constitute one transformer block. The outputs are then fed to the next block. This process can be repeated as many times as desired. In GPT-2’s case, this is repeated 12 times.

- At the output end of the last transformer block, we apply a softmax layer to convert the outputs to probabilities. This represents the probability of a particular token being the next token in an input sentence.

This completes the architecture. There are a couple of details I left out above because I felt they would disrupt the flow and are of minor importance. They are as follows:

- Add and Norm: There are several layers of Add and Normalization, how this works is we take the input before MLP or attention respectively and add it to the output, and then normalize the values to some range ex. between 0 and 1. The point here is to avoid vanishing gradient and exploding gradient problems by feeding the original inputs through the model and then ensuring output numbers don’t get too large.

References

3Blue1Brown. (2024, May 27). How word vectors encode meaning [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJtFZwbvkI4

Esmailbeigi, R. (2023, January 20). BERT, GPT, and BART: A short comparison. Medium. https://medium.com/@reyhaneh.esmailbeigi/bert-gpt-and-bart-a-short-comparison-5d6a57175fca

Liang, D., & Klein, D. (n.d.). Transformer explainer. Polo Club of Data Science, Georgia Institute of Technology. https://poloclub.github.io/transformer-explainer/

TensorFlow. (n.d.). Text generation with a transformer. TensorFlow. Retrieved June 1, 2025, from https://www.tensorflow.org/text/tutorials/transformer#the_cross_attention_layer

user3667125. (2020, August 16). Answer to “Why does this multiplication of Q and K have a variance of d_k, in scaled dot product attention?” Artificial Intelligence Stack Exchange. https://ai.stackexchange.com/a/25057

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 5998–6008). https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762